Rhianna Redclift

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

This recipe from Tully’z Kitchen is your ticket to the ultimate authentic creamy vegan butter chicken curry – nutritious, flavoursome, and...

Sweet, sticky deliciousness is the best way to describe this pudding. Dates are an amazing source of vitamins and minerals, energy and fibre.

Who doesn't love a big bowl of steaming noodles? Try this healthier version of one of our favourite Thai dishes.

In nature, colour can be an indicator of a high concentration of nutrients, and these veggie patties are no exception. The traffic light colours...

If you haven’t used liquid smoke before, you’re in for a real treat. You can find it at most specialty grocers, and it adds an amazing BBQ...

Loaded with fibre and healthy fats, these bliss balls are the perfect mid-morning or afternoon pick-me-up snack!

What’s better than a homemade treat? One that someone else has made especially for you! Delight your loved ones with these festive beauties...

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

Many women have low iron stores, but it’s not because we don’t eat meat. Here’s what you need to know to maintain optimal levels.

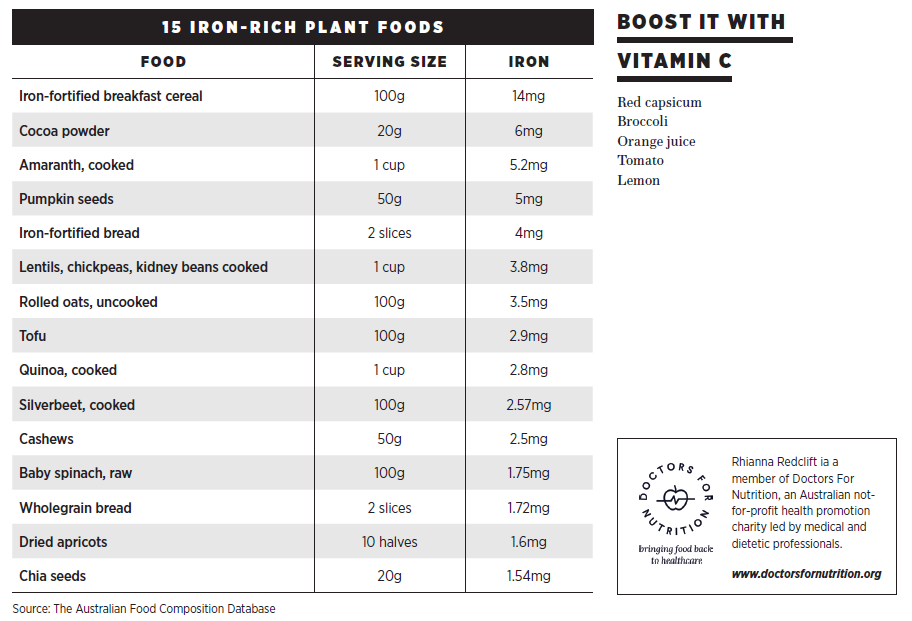

There is a misconception that getting enough iron on a plant-based diet is difficult. The reality is, with a little thought, meeting your iron requirements is relatively easy. Plant foods happen to be abundant in this vital mineral. For example, 100 grams of cashews contain almost twice the amount of iron as 100 grams of cooked beef. When you consider this alone, it’s not hard to see why vegans and vegetarians can often consume more iron than people who choose to eat animal products.

Iron is an essential mineral found predominantly in our red blood cells. It is essential to transport oxygen from our lungs to all the tissues in our body. We also require iron for energy metabolism, neurological development and hormone synthesis.

There are two forms of dietary iron: haem iron and non-haem iron. Non-haem iron is found in plant foods and iron supplements. Haem iron, on the other hand, is found in animal flesh such as red meat, seafood and poultry. Haem iron is more readily absorbed than non-haem iron, which probably contributes to the misconception that plant-based diets do not provide enough iron.

What doesn’t get talked about so much is that an iron overload has been linked to inflammatory conditions such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease, among others. The human body cannot rid itself of excess iron and therefore has evolved to regulate absorption to help prevent this from happening.

However, due to haem iron’s high bioavailability and the fact that it bypasses the body’s finely tuned iron-regulation systems, it is more likely to lead to high iron stores. Non-haem iron on the other hand is carefully balanced based on the body’s need for iron. This clever system is a protective measure for prevention of iron overload and indicates that human physiology is very well adapted to consuming iron from plant sources.

While non-haem iron is regulated by our bodies, it is also less easily absorbed. This is largely due to the influence of other compounds found in plant foods. The key to meeting your iron needs on a plant-based diet is to minimise foods that might impede your absorption and maximise those which can increase it.

If our consumption of dietary iron is chronically low, our stores become depleted and this decreases our haemoglobin levels. Once our stores are exhausted, this results in iron deficiency anaemia. This condition limits the body’s ability to transport oxygen to our cells, resulting in symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, reduced immune function, and hair loss.

Iron deficiency anaemia is one of the most common nutritional deficiencies in the world and affects approximately 25 percent of the population globally – and it is important to note those following a plant-based diet are no more at risk than omnivores. Iron deficiency is more prevalent in young women, largely due to blood loss during menstruation, and, in Australia, women who follow calorie-restricted diets for weight loss are most vulnerable.

While some studies have shown that, compared to omnivores, those following plant-based diets can have iron stores at the lower end of the normal range, in Australia, this does not mean they are at a greater risk of iron deficiency anaemia. In fact, the lower iron stores found in vegetarians and vegans could actually be beneficial given that research has found high iron stores may be associated with an increased probability of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes.

The Australian Recommended Dietary Intake for iron is eight milligrams for adults and 18 milligrams for women of menstruating age.

Even though vegans and vegetarians tend to consume similar, and often more, iron than omnivores, they still tend to have lower iron stores. This would suggest that those following plant-based diets have higher iron requirements. Based on information provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council and New Zealand Ministry of Health nutrient reference values, those following a plant-based diet may need 1.8 times more iron than omnivores due to the types of iron consumed and their rates of absorption.

However, this guidance is derived from limited research on vegetarian diets. These recommendations were based on a study in which the vegetarian diet was high in iron inhibitors and limited in vitamin C rich fruits and vegetables, which are essential for regulating the uptake of non-haem iron from the gastrointestinal tract. Until we have clear science on how much more iron vegetarians require, it is important to focus on including plenty of iron-rich foods while also optimising our diet to increase absorption of this important nutrient.

Tea, coffee and wine can all reduce the absorption of iron due to their tannin content, which binds to iron and causes it to be excreted from the body. Because of this, it is recommended we avoid drinking these beverages within an hour of mealtimes.

Additionally, phytates found in many vegetables, legumes and wholegrains can also reduce iron absorption, particularly in those with poor diets. We can all combat this by cooking, soaking, sprouting, leavening, and fermenting our plant foods. These processes can all help to reduce phytate levels.

You could try sprouting some of your legumes, eating tempeh and other fermented foods, and consuming wholegrain bread. It is important to understand that phytates are also powerful antioxidants and may reduce the risk of chronic health diseases and some forms of cancer, so they also play a role in a healthy diet. You don’t want to avoid these compounds altogether, rather consume them as part of a varied diet.

Some of the best plant-based sources of iron include legumes, soy products such as tofu and tempeh, nuts, seeds, wholegrains, dried fruits such as figs, leafy green vegetables, oats and fortified wholegrain breakfast cereals. To minimise the effects of phytates on iron absorption, it is important to consume vitamin C rich foods with meals. This can enhance the uptake of iron up to six times in those with low iron stores.

To increase iron absorption, you can try cooking legumes in a tomato-based sauce, include vegetables on your plate such as capsicums, cauliflower and green vegetables, or enjoy half a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice (with the pulp) alongside your meals. Even the citric acid in a squeeze of lemon over your food will help to increase your iron levels.

If you are concerned about your iron intake, discuss this with your doctor and dietitian. If a blood test reveals you are low in iron, you may need to take a supplement to help bring your iron stores back up to the recommended range. There are also certain health conditions and medications that can affect uptake of iron, so this should also be considered. It is a good idea to speak to your medical practitioner before taking any supplements. If supplements are required, your doctor can suggest the appropriate iron supplement that is best for you.

Making whole plant foods the cornerstone of your diet will provide your body with an array of micronutrients, which all work together to meet your nutritional needs. As with all balanced diets, it’s not about meeting your requirements for any one isolated nutrient from any one food source, but about eating a variety of foods in order to get the greatest overall nutritional benefit from what you eat.

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.