Simon Hill

Nourish magazine issue 76

Buy Now

Whether you call it porridge or oatmeal, take this timeless breakfast classic to the next level with Simon Hill’s supercharged version.

This bowl of goodness combines a rainbow of cooked and raw veggies with succulent tempeh, wild rice, and sauerkraut for the ultimate gut-loving...

Newsflash: all plants contain protein and all nine amino acids. Chances are, you’re meeting or exceeding your protein needs on a plant-based...

Are carbs really making us fat and sick? Is it possible a high-protein, high-fat diet is the holy grail of a healthy body? It’s time to...

Nourish your body from the inside out! Building a happy gut microbiome will benefit your overall health and wellbeing.

Somewhere between a smoothie and ice cream, this pumpkin pie nice cream tastes divine and makes for a refreshing, nutritious breakfast, snack, or...

So many nuts, so many ways to use them! They’re nuturally high in protein and add a hearty lusciousness to any dish.

This refreshing, sparkling cocktail with a tint of pink is like summertime in a glass. Perfect for elegant entertaining.

Smashed avocado on toast is perhaps the most popular breakfast or brunch item out there, and as much as we love the mighty avo, it generally has...

Panzanella is a popular Tuscan salad starring stale or dry bread drenched in a classic vinaigrette dressing. This version features colourful...

Colourful and nutritious, this hearty Moroccan-style salad combines spiced roast veggies, chickpeas, massaged kale and plump sultanas with an...

This lemonade can be made with any fresh summer berries you have on hand. It’s quick and easy, too – just remember to make the pressed berry...

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

Does life feel like an uphill battle? Maybe it’s time for change

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

Whether you call it porridge or oatmeal, take this timeless breakfast classic to the next level with Simon Hill’s supercharged version.

TIP: You can make ultra-nutritious chia berry jam in less than ten minutes by heating fresh or frozen berries in a small pan along with water, chia seeds, and (optionally) maple syrup to taste. Check out this recipe by Dr Tasia Cech for quantities and steps.

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

Does life feel like an uphill battle? Maybe it’s time for change

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

This bowl of goodness combines a rainbow of cooked and raw veggies with succulent tempeh, wild rice, and sauerkraut for the ultimate gut-loving boost.

TIP: If you’re new to tempeh, it’s a great idea to try several kinds to help discover your own favourites. There’s a good range to choose from in the fridge section at most grocery shops, including spiced, smoked, and marinated varieties.

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

Does life feel like an uphill battle? Maybe it’s time for change

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

Newsflash: all plants contain protein and all nine amino acids. Chances are, you’re meeting or exceeding your protein needs on a plant-based diet.

Protein is made up of amino acids, which are often called the building blocks of life. When we consume protein, our digestive system breaks the protein molecules down into their constituent amino acids, which are then absorbed by our bodies and used to create over 30,000 different proteins, from antibodies to hormones to enzymes to transport molecules, and much more, that are essential to our bodies’ functioning. Proteins are defined by the amino acids that they contain and the sequence in which the acids occur.

There are two major classes of amino acids: essential amino acids (EAAs) and non-essential amino acids (NEAAs). Like essential and non-essential nutrients, NEAAs are those our bodies can manufacture on their own, and therefore we do not require them in our diet. EAAs, on the other hand, cannot be produced by our bodies, so we must obtain them from the food we eat. If we supply our body with sufficient EAAs, they will work together with the NEAAs to manufacture all of the protein molecules we require.

EAAs are found in different concentrations in plant and animal foods, which leads to these foods sometimes being described as ‘incomplete’ and ‘complete’ proteins. These terms would make most people think that plant foods are missing certain EAAs, but that is not true – all plants contain all nine EAAs.

The term ‘incomplete’ only means that the quantity of one or more of the EAAs in a particular plant food is lower than what is considered optimal. The problem with this narrow view of protein consumption is that, instead of looking at the overall dietary pattern, it judges a single food in isolation.

The only way this could ever be a problem is if you only ate a single source of protein, such as rice or nuts, as your sole source of calories – and even then, if you were consuming adequate calories, you would still easily be getting all EAAs in the required amounts, except lysine, which would just fall short of the daily recommendations. Fortunately, this is not how we eat and there are plenty of plant foods that are bursting with lysine – beans, lentils, tempeh, and tofu, to name just a few.

You may be wondering whether this means you need to make sure you are eating ‘complementary’ protein sources of amino acids in each and every meal you have. Fortunately, there is no need to become hyper-focused on your amino acid intake, especially if you are eating a diverse range of plant foods. Your body has a constant pool of amino acids from the food you consume across the day.

While it’s clear that people eating a wholefood, plant-based (WFPB) diet can easily get enough protein, the other aspect of protein quality that should be considered is its digestibility. You may have even heard someone say that plant protein is less digestible than animal protein. This belief comes from various studies that use one or both of the two main evaluation methods that rate protein digestibility, the PDCAAS and DIAAS. While these scoring systems are somewhat helpful in assessing protein quality, they are far from perfect.

Fortunately, as science advances, we are beginning to see more precise studies conducted in humans and, so far, animal and plant protein digestibility only differ by a few percent. It’s for these reasons that global protein recommendations are not any higher for vegetarians or vegans than others.

Even if we assumed that on average plant protein was around 10 percent less digestible than animal protein (to play it safe), increasing our protein intake by 10 percent above the recommendations as an insurance policy is easily achieved on a WFPB diet. For most people, this is only around five to 10 grams of protein more per day – equivalent to that found in two to three tablespoons of hemp seeds.

The US Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2016 position paper emphasised that “vegetarian, including vegan, diets typically meet or exceed recommended protein intakes, when caloric intakes are adequate”, a finding supported by multiple studies that have analysed the protein intakes of vegetarian and vegan populations across the world.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) protein recommendations for the average adult are set out as grams per kilogram of body weight. Men require slightly more protein than women, and the recommended dietary intake (RDI) increases slightly for people 70 and older, due to their increased risk of muscle loss and frailty. Protein requirements are also higher during pregnancy and lactation to help promote healthy growth and development of a baby.

It’s important to note that the protein recommendations are based on the amount of protein required to meet basic nutritional needs and prevent deficiency, and have not been tailored for people following a WFPB diet. To illustrate what this looks like in terms of protein per day, let’s go through an example using a 35-year-old woman who weighs 65 kilograms, spends a large percentage of their day sitting, and doesn’t perform intensive exercise. Working from the NHMRC protein recommendations, this woman’s recommended daily protein intake is approximately 49 grams (65 kilograms x 0.75 grams). If we were to add an extra 10 percent as an insurance policy, to factor in the slightly lower digestibility of plant protein, it would increase her daily requirement to approximately 54 grams.

What about someone who is more physically active: how much protein do they require? There is a good amount of science to suggest that increasing protein intake is beneficial to those seeking improved muscle recovery, strength, growth, and body composition. If this is you, my general recommendation is for plant-powered endurance athletes to aim for around 1.5 grams per kilogram per day, and strength athletes to aim for around 1.8 grams per kilogram per day, which is at a level that will maximise muscle growth and recovery while still allowing sufficient room to consume all food groups.

These ranges are based on the best science available today, including a 2018 meta-analysis that looked at all of the science on optimal protein consumption for muscle repair and growth. Many of these studies looking at protein consumption and muscle growth are based on people consuming animal protein as part of an omnivorous diet. I’ve accounted for the slightly lower bioavailability of plant protein in my recommendations, along with the fact that there is an upper limit of protein set by the NHMRC of 25 percent of total calories. Above this level, there is the potential for calories from protein to displace calories from other healthful food groups.

While all plants contain protein, legumes are going to provide most of your protein when you eat a healthy WFPB diet. I really cannot think of a healthier substitute for animal products! They contain all EAAs in health-promoting ratios and are incredibly rich in fibre, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients, while being naturally low in saturated fats and free from cholesterol.

![]()

|

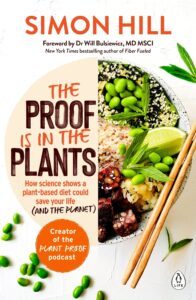

This article is an edited extract from The Proof is in the Plants by Simon Hill. Published by Penguin Life. |

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

Does life feel like an uphill battle? Maybe it’s time for change

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

Are carbs really making us fat and sick? Is it possible a high-protein, high-fat diet is the holy grail of a healthy body? It’s time to separate the fact from the fiction.

Chances are you’ve heard about the ‘Ketogenic Diet’ or keto diet, which is a reincarnation of super low carbohydrate diets such as the Atkin’s Diet or the South Beach Diet. And, credit where credit is due here – the advocates of this dietary framework have been extremely clever with their marketing, resulting in wide circulation of their key claims. Given these claims centre on promises for a body primed for burning fat and better blood glucose control, it’s easy to see why many people who want to lose weight or manage diabetes find this diet attractive. But are these claims supported by science? I think it’s time we separate fact from fiction when it comes to the keto diet.

Before we jump into the science, it’s important to understand the basic premise of this dietary framework. A ketogenic diet consists of a very low amount of carbohydrates (20–50g per day), moderate amounts of protein, and a very high amount of fat (70% or more of total calories). Because the body is deprived of its primary fuel source, glucose, it transitions to a state of ketosis, whereby it begins to produce compounds called ketones that are used for energy. Essentially, this is a survival mechanism that enables the body to keep creating energy from a secondary source – fat – until the person finds carbohydrates again. As you can imagine, this would have been very beneficial for our ancestors when food supply was not guaranteed. But how healthy is it as a strategy for weight loss or managing lifestyle disease?

In theory, the Ketogenic Diet claims to switch your body from one that produces energy from glucose (carbohydrates) to a body that ‘burns fat’ as its energy source. So, that would mean greater fat loss, wouldn’t it? Happy days! But unfortunately, that’s not how it works. Unless you are in a calorie deficit (eating less calories than you use), a state of ketosis simply uses energy from dietary fat, not stored fat. And fat burning is very different to fat loss. This is a point that many keto advocates gloss over. To tap into your body’s fat stores, you need to burn more calories than you consume. In fact, a metabolic ward study that compared a ketogenic diet with a high carbohydrate diet of the same total calories found zero difference in body fat loss. The people in this study, just like anyone in ketosis, used fat as their primary source of energy. But regardless of diet, unless they were in calorie deficit they did not burn stored body fat. So unless you are in calorie deficit on the keto diet, you’re simply using the fats in the avocado or coconut oil you just ate (or bacon and butter for non vegans).

However, people do seem to anecdotally lose weight when they switch to a ketogenic diet. Why? There’s two major reasons. The first one is obvious – glycogen. The average person stores about 500 grams of glucose in their muscles as glycogen. Each gram of glycogen attracts three grams of water. Therefore, when you switch to a ketogenic diet your body uses all of its glucose stores before going into a state of ketosis. This process alone results in a drop of about two kilograms. But this is purely scale weight and is not a reflection of fat loss. I can understand how this very sudden drop in scale weight acts as an initial motivator and hooks people in. Unfortunately though, it’s nothing more than a facade, and many studies show that maintaining glycogen stores is crucial for optimal recovery, performance and overall exercise capacity.

The second reason the keto diet helps people lose weight is actually a good one. Because it encourages only consuming a miniscule amount of carbohydrates per day, by default this means people cannot eat their favourite refined junk foods. So, all of a sudden chocolate bars, doughnuts and fried potato chips are off the menu. This sees many people fall into a calorie deficit. But let’s remember – this isn’t some magic weight loss process. You can in fact remove refined junk foods while still eating healthy carbohydrate-rich foods and achieve a similar result.

Perhaps the most concerning of the claims made by keto advocates is the idea that the diet can reverse insulin resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Properly addressing the science surrounding this is outside of the scope of this story, however, to reverse insulin resistance or Type 2 Diabetes you need to improve your body’s ability to tolerate carbohydrates. This can be achieved by changing the types of food you eat with or without the presence of weight loss. While a ketogenic diet may help control blood glucose, without weight loss, it does not improve insulin sensitivity. So why is this a problem? It means you need to continue to eat a low carbohydrate diet for the rest of your life because you have not addressed the underlying cause of the disease. In fact, this is likely to have been made worse by higher amounts of ectopic fat stores in muscle and liver cells.

On the other hand, unlike the ketogenic diet, a whole food plant-based diet that is low in fat has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity without requiring weight loss. Remember, to treat the cause of insulin resistance or Type 2 Diabetes, you need to improve tolerance to carbohydrates – not simply remove them. Changing the food a person eats can achieve almost instant changes in insulin sensitivity. Several trials have been published whereby Type 2 Diabetics who adopt a whole food plant- based diet that is low in fat have been able to completely come off their medications. The other thing to keep in mind is that the number one cause of death for diabetics is cardiovascular disease. The lowest levels of cardiovascular disease are consistently found among populations that get the majority of their calories from whole food plant sources of carbohydrates. So that then begs the question: What is the cost associated with leaving healthy carbohydrate-rich whole foods off the menu like whole grains, fruits and legumes for the rest of your life if you are following a keto diet to manage insulin resistance?

Let’s jump straight to the punchline here. A ketogenic diet will increase your risk of chronic disease. There are no populations who consume a low-carbohydrate diet that show longevity. Research instead suggests people adopting such diets long term have a higher risk of premature death. Low-carb advocates will talk about the Inuit Eskimos, a population who traditionally consumed a very high fat diet made up of almost exclusively animal products to disprove this. However, it’s been well documented that claims this population experienced a low incidence of cardiovascular disease were based on anecdotal rather than empirical scientific evidence. In fact, compared to non-Inuits from nearby populations, the Inuit population actually have the same risk of heart disease, twice the risk of stroke, and a shorter life expectancy of approximately 10 years. Studies have even reported the presence of heart disease in frozen Eskimo mummies dating back to over 1,000 years ago.

Basing recommendations for a low carbohydrate diet on anecdotal evidence from the Inuits ignores what we know about high fat diets and cholesterol as well as a plethora of evidence that we have on how the longest living populations in the world eat. The typical ketogenic diet contains foods associated with increased LDL cholesterol and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and that’s exactly what the science shows. A recent study compared a ketogenic-style diet (less than 20g of carbohydrates per day) to a control diet and found the low-carbohydrate diet subjects experienced a 44 per cent increase in LDL cholesterol in just three weeks.

We also know that people who consume higher amounts of dietary fibre (found in carbohydrate-rich plant foods) and lower amounts of total dietary fat (particularly saturated fat) experience significantly less risk of developing major chronic diseases. Adopting a ketogenic diet, and therefore restricting your dietary fibre intake, is certainly risky business when it comes to overall health.

One of the biggest problems with low- carbohydrate diets is that they are not sustainable and almost always lead to long term weight gain. We know from several studies, randomised trials, and population studies, that adopting a whole food plant-based (or even plant-focused) diet helps people maintain a healthy body weight without having to calorie count. And, when talking about sustainability, we also need to touch on the health of our planet. Typically, a ketogenic diet includes large amounts of animal products (such as fatty cuts of meat, full-fat dairy products, and eggs), which we know require greater water inputs and produce more greenhouse gas emissions than plant-based foods. For example, for an equal amount of protein, the production of cheese produces approximately fourteen times more greenhouse gas emissions than that of legumes. In its typical form, a keto diet places a greater strain on our environment. And while a vegan keto diet at a high level appears to be better for environmental health and animal welfare than a typical keto diet, there is still a lot more science needed to before we can confidently recommend it as a safe and healthy dietary framework to follow long term.

In summary, there is no evidence to suggest that a typical ketogenic diet is better than any other diet for weight loss when calories are matched. And there is zero data to suggest this is a healthy way to eat long term. A carbohydrate-rich whole food plant-based diet, on the other hand, is sustainable for both you and the planet, and comes with a host of health benefits. My recommendation is to look past the sexy marketing messages of the ketogenic diet and veto the keto.

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

Does life feel like an uphill battle? Maybe it’s time for change

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

Nourish your body from the inside out! Building a happy gut microbiome will benefit your overall health and wellbeing.

Although he did not have the scientific and medical sophistication we now boast, more than 2,000 years ago Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, had already clued into the fact that many diseases begin in the gut. We now have conclusive scientific evidence that the bacteria living in our guts play an essential role in determining our health. This includes increasing our mental health, reducing inflammation, decreasing the risk of diabetes, facilitating the efficiency of cancer treatments, and helping us maintain a healthy weight. I think it’s about time we all learned how to take care of our gut so that we can nourish our bodies from the inside out.

Building a healthy gut starts with eating a vast variety of plant foods. The variety is absolutely crucial for diversity in our gut microbiota. Therefore, the best thing you can do to ensure a thriving and happy gut is to make sure you are constantly eating different plants rather than sticking to the same three vegetables with every meal.

Prebiotics are a kind of plant fibre that along with resistant starch and phytochemicals feed the good bacteria in our stomach and therefore stimulate the growth of healthy bacteria. Probiotics are the bacteria themselves. So, to ensure your good bacteria is thriving and multiplying, feed it prebiotic-rich foods. Think apples, onions, garlic, banana, oats, whole grains and asparagus. Probiotic rich foods to look out for include kimchi, sauerkraut, miso and tempeh.

If you’re recovering from an infection or have taken a course of antibiotics, probiotic pills can help you re-establish a colony of good bacteria. Otherwise, there is insufficient evidence that popping a probiotic pill can do us any good.

The increased use of pesticides in foods is one of the known culprits behind our overall loss of gut diversity and our declining gut health. Therefore, eating mostly organically grown foods can help reduce the amount of pesticides we ingest. And with the prices of organics going down each year, it has never been more affordable or easy to stock up on pesticide-free foods.

Aim to eat 30g of fibre a day. My favourite fibre-rich foods are lentils, beans, chickpeas, brown rice, oats, quinoa and chia seeds. While eating a fibre-rich plant-based diet is undoubtedly health promoting, if you’re not used to consuming a lot of vegetables, legumes and fruits, you may notice a significant increase in flatulence and bloating due to the increase of fibre. But these symptoms typically settle after a short time. Try to be patient with the process.

The medical community continues to unearth connections between the health of our microbiome and our overall health and wellbeing, so it’s worth putting in the effort today to take care of your gut. It will continually pay off in the long term.

In the fast-paced and demanding world we live in, finding moments of stillness and calm can be challenging. In an attempt to find a little peace...

If you want to get your gut in order, Dr Will Bulsiewicz is the expert to help you sort out fact from fiction. This is the gut-health cheat sheet...

Does life feel like an uphill battle? Maybe it’s time for change

Spraying sheets and pillows with calming scents can be a wonderful aid to slumber

The next time you go for a walk, discover the wonder of the everyday world around you

A skincare routine can be a way to nourish yourself inside and out

When the clouds converge, practise gratitude for the smallest of glimmers, and learn to dance in the rain.

Subscription Options

to receive regular Nourish updates and offers directly in your inbox.

Interested in partnerships, submissions or providing more detailed feedback? Please visit our contact us page.